Did you know that the sentences you say aren’t just a string of words in an order, but clusters of phrases that build on each other, like building with blocks?

Scientists study the structure of a language and the way words relate to each other, called syntax. The syntax, or form, of a sentence is different from what it means. For example, you can say things that seem like a proper sentence of your language, but that are essentially meaningless, such as Noam Chomsky’s famous example, “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.”

In the same way, the two sentences below mean roughly the same thing, but they have two different structures (though there are nuanced reasons why you might use “active” versus “passive” sentence construction):

“The star player kicked the ball.” versus “The ball was kicked by the star player.”

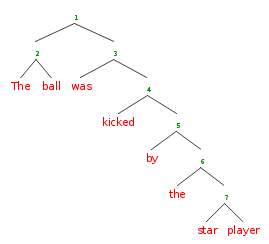

Even though they mean roughly the same thing, some small things about the structure have changed. In the first sentence, the subject is “the star player,” but in the second sentence, the subject is “the ball.”

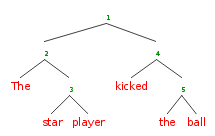

To more closely study a sentence’s structure, linguists draw trees that show how words connect to each other. The places where words connect are called nodes, and these nodes can also connect to each other, building up what linguists call constituents, or phrases. Each node contains every other node and word that is attached below it in the tree. Linguists do this so they can see the hierarchy of the words’ relationships.

Here’s a tree for “The star player kicked the ball.”

And here’s a tree for “The ball was kicked by the star player.”

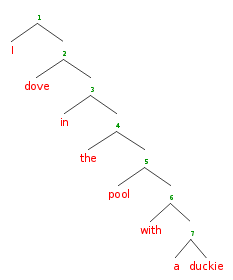

Of course, people can say more complicated sentences too, where the syntax is more complex. Sometimes, the exact same sentence can even have more than one meaning, depending on its internal (invisible!) structure.

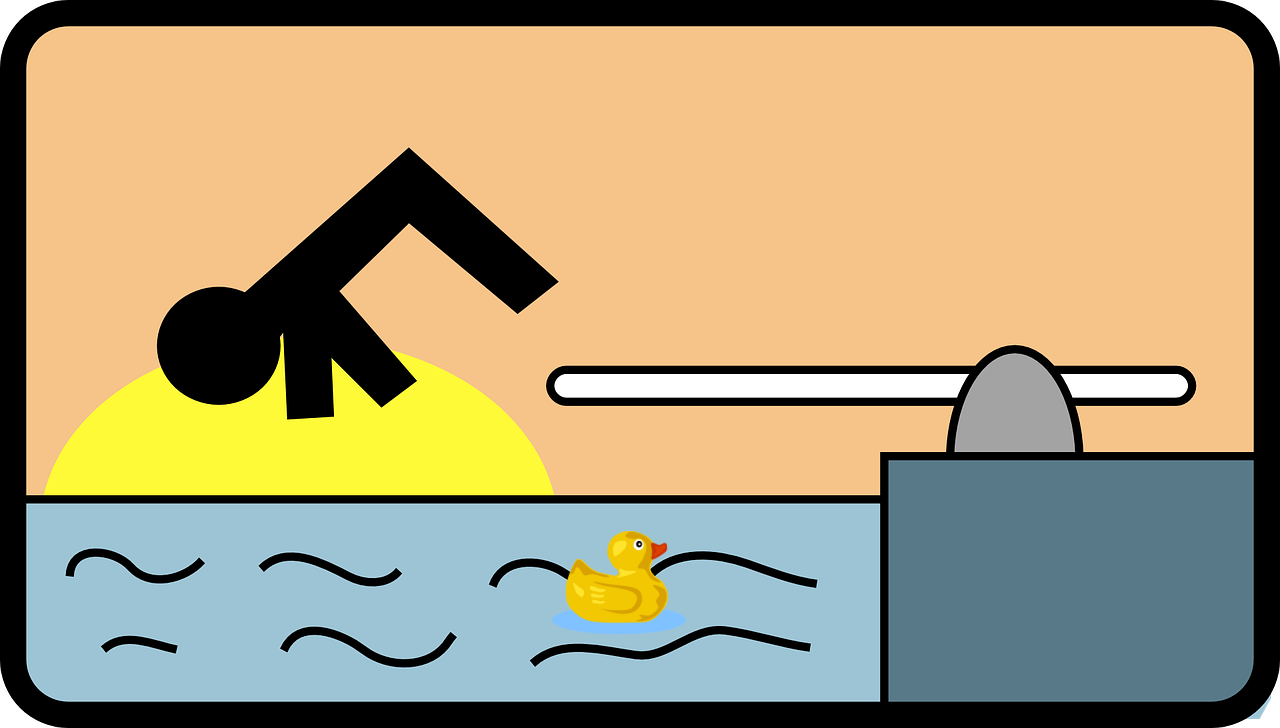

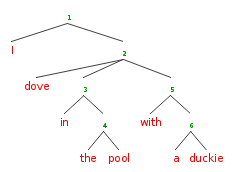

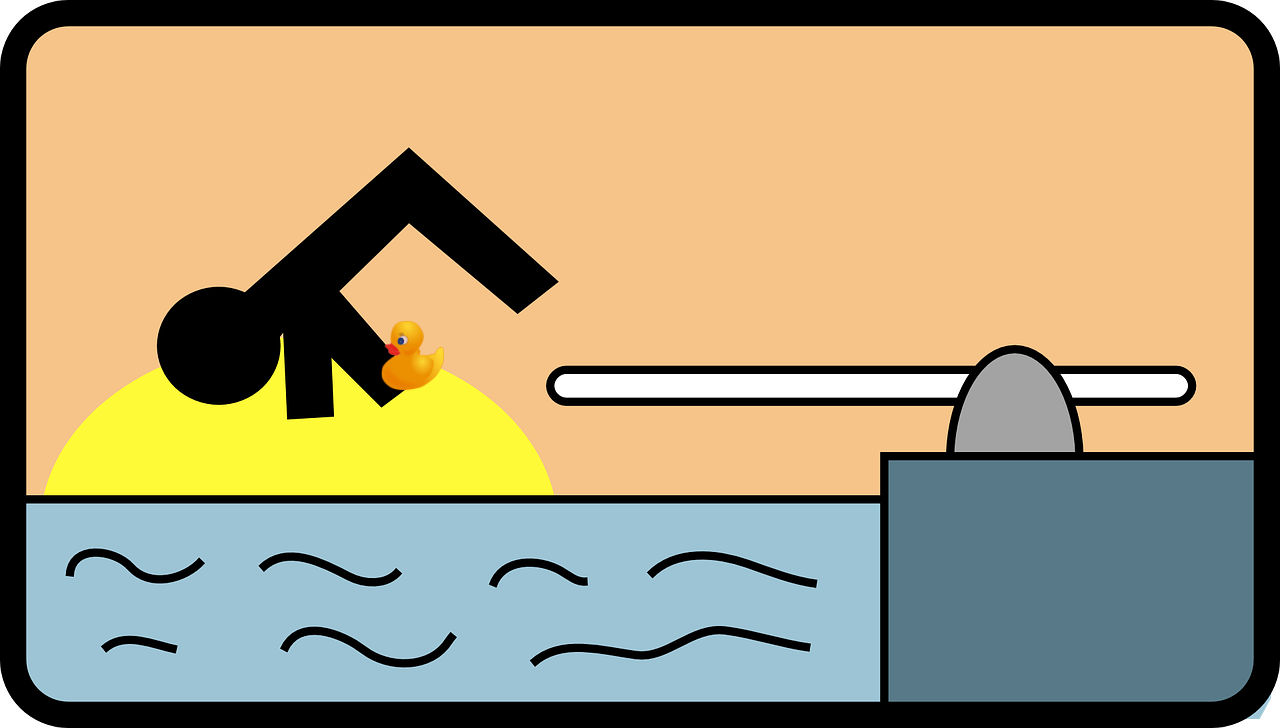

For example, the sentence “I dove in the pool with the duckie” could either mean that the pool I dove in had a duckie in it, or that I was holding a duckie as I dove. The trees look different for each interpretation because the words are clustered together differently.

Here’s a picture and its corresponding tree for the interpretation where the duckie is in the pool:

And here is the picture and its corresponding tree for the interpretation that the duckie is held by the diver:

For some languages (like English), word order is very important, and pretty fixed in place. In other languages, word order can shift around more because the structure of the sentence is instead revealed by small pieces of words (morphemes) that are added.

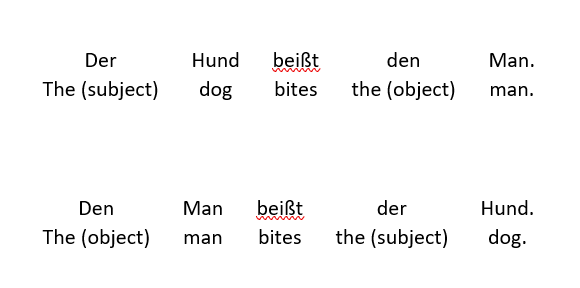

For example, to translate the sentence “The dog bites the man” into German, you could use two different word-orders:

Both word orders mean that the dog bites the man; the difference lies in what word for “the” is used. In English, you can figure out what the subject is (and therefore who’s doing the biting!) because it appears first in the sentence; in German, the subject is marked by the form of the determiner (sometimes called an article), the: in this case, “der.”

Syntax is a wide and deep field, and some linguists study it for their entire lives. Some baby language researchers investigate when babies and toddlers learn the different complexities of their syntax!

Aahnix Bathurst

Editor/publisher

Aahnix is a Project Coordinator in the Bergelson lab at Duke University