As a pet owner, I often find myself wondering if my dogs are actually “saying” what I have interpreted from their barks, whines, and sighs. When they bark at the door to go outside or at the window when a car passes by, are they using language that I just can’t understand?

While dogs definitely communicate with people and each other, scientists’ definition of language is a little more specific. Humans use language as a precise set of symbols (i.e. gestures, sounds, written characters) to express themselves, influence others, and even make jokes. Each language has its own set of symbols, but different languages can have commonalities, like similar types of patterns for combining symbols (e.g. English and Spanish sharing many of the same sounds for making words). To be a language, a communication system has to have a few features: it has to be compositional and productive, which means that you can combine the symbols (ie., words) in many ways to make up and understand completely new sentences (Robins). For instance, you’ve probably never heard the sentence “scholarly ants outsmart us again.” There is no limit to what we can communicate! Because of these considerations, language is a uniquely human ability. So, sadly, my dogs–and all other animals–are not capable of using language, although there are videos that claim otherwise: Bunny the talking dog on TikTok, Koko the gorilla that used sign language, and Apollo the talking parrot.

It may sound selfish to claim language is strictly human, but there is evidence to support that we are the only species that has developed an ability to learn and use it– after all, there are many species of animals with abilities humans don’t have, like bees seeing ultraviolet light (Shipman) or dolphins using echolocation (Fitch, “Animal Cognition”). It also doesn’t mean that animals aren’t smart: we think animals are capable of having many conceptual representations, or thoughts about the world around them, but they just cannot communicate all of these thoughts to others in the detailed way we do (Fitch, “Animal Cognition”).

For example, birds can remember where they hid a stash of food and use that memory to go locate the food without being prompted (Fitch, “Animal Cognition”), showing that animals have detailed memories for resources, but they can’t give another animal directions in words. These representations of concepts are also less complex than those of humans. For example, chimpanzees, dogs, and even parrots can match signals to concepts, but humans are distinct in their ability to infer an implicit meaning of what is said by using context, rules of communicative intent, and theory of mind, or the capacity to embody others’ beliefs and wishes (Fitch, “Empirical Approaches”). Humans have concepts that are much more sophisticated and we can turn the concepts we possess into complex thoughts with hierarchical structure–each thought about a concept is developed from previous representations to form meaning and value–to communicate them for others to understand (Fitch, “Animal Cognition”). Though animals can communicate through sounds and gestures (e.g. a wolf’s howl signals their location to their pack, and danger to its prey), what they can convey is limited.

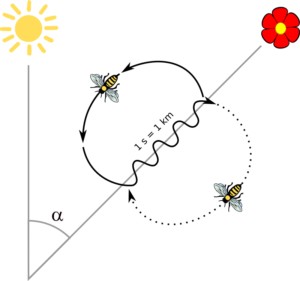

Honeybees have elaborate dances to communicate the locations of flowers and other things, like water, but can’t describe color despite having better color vision than our own. Their dances are similar to what is termed language displacement in humans (note that honeybees are the rare exception in terms of animals capable of doing this). We are capable of talking about things that aren’t readily accessible in the moment (i.e. past or future events, hypothetical situations) (“Language, Displacement”). This phenomenon also describes why we can have conversations merely for the social function of communication, like asking questions or making jokes. I have yet to see a honeybee make another honeybee giggle, unfortunately.

Animals also lack the physical features necessary for speech production. Birds make sounds from their syrinx, but they do not have lips or teeth, or articulable fingers, which are necessary for detailed speech articulation (Robins). Even our closest evolutionary relatives (who share >90% of our DNA) don’t have the same kinds of brain structures we do for processing and producing language. For instance, a part of the brain involved in language in humans is Broca’s area. Macaque monkeys have a similar region, area 44, which shares functional similarities in the involvement in hand and mouth movements unrelated to language, but for macaques, there is no additional function for speech production (Rilling).

If you are on TikTok, you may have heard of Bunny the “talking” dog. As of May 2021 she uses 92 words, but her buttons don’t really tell us if she knows the words she has been trained to use (Madden). She also doesn’t combine her words in structured, regular patterns the way people do. Bunny is not talking–she just uses an expanded set of symbols to communicate her needs to her owner, and our understanding of what she wants is heavily subject to interpretation by her owner. Without her owner’s “translation,” you probably wouldn’t get a specific, unambiguous message from Bunny the way you can understand sentences even when you’re talking to humans you’ve never met. So, unlike my dogs, Bunny doesn’t have to bark to share what is going on in her mind, but similarly she has learned to navigate the language barrier to get what she wants.

References

@apolloandfrens. “What color is the #rock #talkingparrot #talkingbird #parrot #birds #smartbird #learning #learningtotalk #speech.” TikTok, 15 Jan. 2023, https://www.tiktok.com/@apolloandfrens/video/7188612165295721774?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7189994858173400619.

@whataboutbunny. “Our little concerned bb #soundsensitivity #aic #fluentpet #smartdog #dogteaching.” TikTok, 29 Dec. 2022, https://www.tiktok.com/@whataboutbunny/video/7182659173690379566?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7189994858173400619.

Fitch, W. Tecumseh. “Empirical Approaches to the Study of Language Evolution – Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.” SpringerLink, Springer US, 1 Feb. 2017, https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13423-017-1236-5.

Fitch, W. Tecumseh. “Animal Cognition and the Evolution of Human Language: Why We Cannot Focus Solely on Communication.” The Royal Society Publishing, 18 Nov. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0046.

Language, Displacement, Structure Dependence, Creativity. https://is.muni.cz/el/1441/podzim2008/AJ2BP_USAJ/um/2_Language__displacement__structure_dependence.pdf.

Madden, Emma. “The ‘Talking’ Dog of Tiktok.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 27 May 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/27/style/bunny-the-dog-animal-communication.html.

Rilling, James. “Broca’s and Wernicke’s Areas.” Broca’s and Wernicke’s Areas | Center for Academic Research and Training in Anthropogeny (CARTA), https://carta.anthropogeny.org/moca/topics/brocas-and-wernickes-areas#:~:text=It%20has%20been%20suggested%20that,%2C%20respectively%2C%20of%20human%20language.

Robins, Robert Henry. “Language.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 16 Aug. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/topic/language.

Shipman, Matt. “What Do Bees See? and How Do We Know?” NC State News, 27 July 2011, https://news.ncsu.edu/2011/07/wms-what-bees-see/#:~:text=Bees%2C%20like%20many%20insects%2C%20see,very%20good%20at%20seeing%20edges.

“Waggle dancing honey bee!” YouTube, uploaded by Flow Hive, 14 Jan. 2019, https://youtu.be/LOZrNs22FAU.

“Watch Koko the Gorilla Use Sign Language in This 1981 Film | National Geographic.” YouTube, uploaded by National Geographic, 22 Jun. 2018, https://youtu.be/FqJf1mB5PjQ.

Daisja Honorable

Author

Daisja is a junior at Duke majoring in Neuroscience with minors in Chemistry and Spanish. She is interested in brain development and language acquisition, especially since she wants to work with children in the future and has been learning Spanish since 2nd grade. Outside of class, she enjoys playing guitar, FaceTiming her dogs, being a mentor, and helping welcome first-year students to Duke through orientation!

Elika Bergelson

Principal Investigator